Here's my response to a column by Maia Szalavitz on the recent recommendation by an FDA panel to change hydrocodone (Vicodin, Norco and others) from Schedule III (where prescriptions can be phoned or faxed in) to Schedule II (where prescriptions have to be printed.)

You can access her column here.

I think the idea is to reduce the number of opioid pain medications circulating in the community. Opioids are now the most prescribed medications in the US. Between 1998 and 2008 the number of prescriptions for hydrocodone (the opioid in Vicodin, Norco and others) increased 53%, from about 80 million to 120 million, whereas the increase in other opioids was 20-34%. Hydrocodone accounts for more emergency department visits than any other opioid as well. As someone who treats chronic pain as well as addiction, I don't like the restrictions on schedule II drugs, and I worry about undertreatment of chronic pain. But deaths from overdosing on opioid painkillers has more than tripled since 1990. I think there is a major gap in the continuum of care for people with chronic pain, especially the lack of pain medicine specialists, as opposed to interventional pain specialists, who like to do a lot of very lucrative injections. Strategies to close this gap are needed. As you note, Maia, most opioids used for non-medical purposes come from medications prescribed for someone else. Thus, the strategy to make prescribing them more difficult in order to reduce the availability. The issue is complex and there are no easy solutions. However, one thing I would like to see everyone get behind is that anyone who is addicted to opioids have immediate and affordable access to opioid maintenance therapy with Suboxone or methadone. If we aren't doing that, we aren't getting serious about opioid addiction in America

The internet's voice for professional, scientifically-based treatment of alcohol and other substance use disorders.

Thursday, January 31, 2013

High Level of Pain Among Methadone Maintenance Patients

Epidemiology of pain among outpatients in methadone maintenance treatment programs

Lara Dhingra, Carmen Masson, David C. Perlman, Randy M. Seewald, Judith Katz, Courtney McKnight, Peter Homel, Emily Wald, Ashly E. Jordan, Christopher Young, and Russell K. Portenoy

Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 2013-02-01, Volume 128, Issue 1-2, Pages 161-165

Copyright © 2012 Elsevier Ireland LtdAbstract

Background

This analysis explored the prevalence and correlates of pain in patients enrolled in methadone maintenance treatment (MMT).

Methods

Patients in two MMT programs starting a hepatitis care coordination randomized controlled trial completed the Brief Pain Inventory Short-Form and other questionnaires. Associations between clinically significant pain (average daily pain ≥ 5 or mean pain interference ≥ 5 during the past week) and sociodemographic data, medical status, depressive symptoms, and health-related quality of life, and current substance use were evaluated in multivariate analyses.

Results

The 489 patients included 31.8% women; 30.3% Hispanics, 29.4% non-Hispanic Blacks, and 36.0% non-Hispanic Whites; 60.1% had hepatitis C, 10.6% had HIV, and 46.8% had moderate or severe depressive symptomatology. Mean methadone dose was 95.7 mg (SD 48.9) and urine drug screening (UDS) was positive for opiates, cocaine, and amphetamines in 32.9%, 40.1%, and 2.9%, respectively. Overall, 237 (48.5%) reported clinically significant pain. Pain treatments included prescribed opioids (38.8%) and non-opioids (48.9%), and self-management approaches (60.8%), including prayer (33.8%), vitamins (29.5%), and distraction (12.7%). Pain was associated with higher methadone dose, more medical comorbidities, prescribed opioid therapy, and more severe depressive symptomatology; it was not associated with UDS or self-reported substance use.

Conclusions

Clinically significant pain was reported by almost half of the patients in MMT programs and was associated with medical and psychological comorbidity. Pain was often treated with opioids and was not associated with measures of drug use. Studies are needed to further clarify these associations and determine their importance for pain treatment strategies.

Lara Dhingra, Carmen Masson, David C. Perlman, Randy M. Seewald, Judith Katz, Courtney McKnight, Peter Homel, Emily Wald, Ashly E. Jordan, Christopher Young, and Russell K. Portenoy

Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 2013-02-01, Volume 128, Issue 1-2, Pages 161-165

Copyright © 2012 Elsevier Ireland LtdAbstract

Background

This analysis explored the prevalence and correlates of pain in patients enrolled in methadone maintenance treatment (MMT).

Methods

Patients in two MMT programs starting a hepatitis care coordination randomized controlled trial completed the Brief Pain Inventory Short-Form and other questionnaires. Associations between clinically significant pain (average daily pain ≥ 5 or mean pain interference ≥ 5 during the past week) and sociodemographic data, medical status, depressive symptoms, and health-related quality of life, and current substance use were evaluated in multivariate analyses.

Results

The 489 patients included 31.8% women; 30.3% Hispanics, 29.4% non-Hispanic Blacks, and 36.0% non-Hispanic Whites; 60.1% had hepatitis C, 10.6% had HIV, and 46.8% had moderate or severe depressive symptomatology. Mean methadone dose was 95.7 mg (SD 48.9) and urine drug screening (UDS) was positive for opiates, cocaine, and amphetamines in 32.9%, 40.1%, and 2.9%, respectively. Overall, 237 (48.5%) reported clinically significant pain. Pain treatments included prescribed opioids (38.8%) and non-opioids (48.9%), and self-management approaches (60.8%), including prayer (33.8%), vitamins (29.5%), and distraction (12.7%). Pain was associated with higher methadone dose, more medical comorbidities, prescribed opioid therapy, and more severe depressive symptomatology; it was not associated with UDS or self-reported substance use.

Conclusions

Clinically significant pain was reported by almost half of the patients in MMT programs and was associated with medical and psychological comorbidity. Pain was often treated with opioids and was not associated with measures of drug use. Studies are needed to further clarify these associations and determine their importance for pain treatment strategies.

Wednesday, January 30, 2013

Most Non-Medication Treatments for ADHD Ineffective: New Study

Hot off the presses (or screen), a new review by the European ADHD Guidelines Group found that non-medication treatments for ADHD are not supported by current evidence. Here's the abstract from The American Journal of Psychiatry.

Nonpharmacological Interventions for ADHD: Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses of Randomized Controlled Trials of Dietary and Psychological Treatments

Edmund J.S. Sonuga-Barke, Ph.D., Daniel Brandeis, Ph.D., Samuele Cortese, M.D., Ph.D., et al.

European ADHD Guidelines Group

Objective: Nonpharmacological treatments are available for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), although their efficacy remains uncertain. The authors undertook meta-analyses of the efficacy of dietary (restricted elimination diets, artificial food color exclusions, and free fatty acid supplementation) and psychological (cognitive training, neurofeedback, and behavioral interventions) ADHD treatments.

Method: Using a common systematic search and a rigorous coding and data extraction strategy across domains, the authors searched electronic databases to nidentify published randomized controlled trials that involved individuals who were diagnosed with ADHD (or who met a validated cutoff on a recognized rating scale) and that included an ADHD outcome.

Results: Fifty-four of the 2,904 nonduplicate screened records were included in the analyses. Two different analyses were performed. When the outcome measure was based on ADHD assessments by raters closest to the therapeutic setting, all dietary (standardized mean differences= 0.21–0.48) and psychological (standardized mean differences=0.40–0.64) treatments produced statistically significant effects. However, when the best probably blinded assessment was employed, effects remained significant for free fatty acid supplementation (standardized mean difference= 0.16) and artificial food color exclusion (standardized mean difference= 0.42) but were substantially attenuated to nonsignificant levels for other treatments.

Conclusions: Free fatty acid supplementation produced small but significant reductions in ADHD symptoms even with probably blinded assessments, although the clinical significance of these effects remains to be determined. Artificial food color exclusion produced larger effects but often in individuals selected for food sensitivities. Better evidence for efficacy from blinded assessments is required for behavioral interventions, neurofeedback, cognitive training, and restricted elimination diets before they can be supported as treatments for core ADHD symptoms.

Am J Psychiatry Sonuga-Barke et al.; AiA:1–15

Nonpharmacological Interventions for ADHD: Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses of Randomized Controlled Trials of Dietary and Psychological Treatments

Edmund J.S. Sonuga-Barke, Ph.D., Daniel Brandeis, Ph.D., Samuele Cortese, M.D., Ph.D., et al.

European ADHD Guidelines Group

Objective: Nonpharmacological treatments are available for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), although their efficacy remains uncertain. The authors undertook meta-analyses of the efficacy of dietary (restricted elimination diets, artificial food color exclusions, and free fatty acid supplementation) and psychological (cognitive training, neurofeedback, and behavioral interventions) ADHD treatments.

Method: Using a common systematic search and a rigorous coding and data extraction strategy across domains, the authors searched electronic databases to nidentify published randomized controlled trials that involved individuals who were diagnosed with ADHD (or who met a validated cutoff on a recognized rating scale) and that included an ADHD outcome.

Results: Fifty-four of the 2,904 nonduplicate screened records were included in the analyses. Two different analyses were performed. When the outcome measure was based on ADHD assessments by raters closest to the therapeutic setting, all dietary (standardized mean differences= 0.21–0.48) and psychological (standardized mean differences=0.40–0.64) treatments produced statistically significant effects. However, when the best probably blinded assessment was employed, effects remained significant for free fatty acid supplementation (standardized mean difference= 0.16) and artificial food color exclusion (standardized mean difference= 0.42) but were substantially attenuated to nonsignificant levels for other treatments.

Conclusions: Free fatty acid supplementation produced small but significant reductions in ADHD symptoms even with probably blinded assessments, although the clinical significance of these effects remains to be determined. Artificial food color exclusion produced larger effects but often in individuals selected for food sensitivities. Better evidence for efficacy from blinded assessments is required for behavioral interventions, neurofeedback, cognitive training, and restricted elimination diets before they can be supported as treatments for core ADHD symptoms.

Am J Psychiatry Sonuga-Barke et al.; AiA:1–15

Tuesday, January 29, 2013

DSM5 Substance Use Disorders Part 2

Yesterday, I posted about the changes in diagnosis of substance use disorders (SUDs) in DSM5 by addressing a key point about whether addiction is a disease, and what that actually means. This is second post that derives from a conversation that Maia Szalavitz and I have been having on this topic. You can read her post on this topic here.

2. What about DSM5 and the changes from DMS4? This is mostly a technical question relating to cut points. How many substance-related symptoms or criteria does one have to have before calling it a disease, meaning a focus of treatment interventions? As it turns out, there is no clear cut-point. Essentially, the more symptoms one has, the more likely they are to be associated with distress and dysfunction. Earlier in the course of the disorder (and most cases don't progress beyond mild to moderate disorder), most symptoms are "internal" meaning that the individual struggles with control of ingestion, especially once ingestion starts. (Going over self-limposed limits, persistent desire to quit/cut down, continued use despite internal problems such as heartburn, hangover, nausea.) The only "external" one is driving while intoxicated (no DUI). About 3/4 of people meeting DSM4 criteria for alcohol dependence only have these symptoms, and the problem is resolved after about 3-4 years on average and does not recur. 20 years after onset 40% report low risk non problem drinking. Proportions differ by drug of course, especially in the proportion of ever-users who become dependent (highest for smoking, lowest for cannabis/hallucinogens, intermediate for alcohol.)

We have been studying people in rehab, hospitals and AA for the past 60 years, and then generalizing to people with the disorder in the community who are not in those places. It turns out that people in rehab are those with the most severe, treatment-refractory disease, the most co-morbidity, and the least social support. In terms of the spectrum of severity, the folks in rehab are the equivalent to people with depression or asthma who are hospitalized: a small proportion with the most severe, treatment-refractory illness. The problem is, we've made the mistake of generalizing from that sample to community dwellers, thinking everyone has exactly the same disease. Of course, this is absurd. This mistake has cost us dearly. For example, there are no treatment options for people with milder forms of the disorder, since no one goes to rehab who doesn't have to, usually with significant overt coercion such as a DUI. In SUDs, we are now where depression was 60 years ago. Then the only options you had were the state hospital, where you'd get committed for 6-12 months and get thorazine and ECT, or psychoanalysis which didn't work and was available only to a few. Prozac, in 1988, changed all that. Now, most people with depression go to their family physician and get a prescription for an antidepressant. Obviously this is much less stigmatizing and traumatic that the state hospital. Rehab is essential the state hospital at this point. This is all going to change soon, especially for alcohol.

Another consequence of the peculiar development of ideas about addiction in the US (because of AA, as you (Maia) have pointed out) is that it is all or none, and inevitably severe and progressive. The new (really old and backward looking) definition of addiction by ASAM is an example of that kind of thinking. In your (Maia's) post, you use the word "alcoholic." This term needs to be retired for several reasons. First, it suggests black/white thinking, although the reality is infinite shades of grey when discussing SUDs. Second, it is strongly associated with images of severe, end-stage drunks (another stigmatizing term.) Third, it has no scientific or clinical meaning and is imprecise, being defined by the writer and readers in whatever way this wish.

But rather than only two or three discreet versions of "problem drinking" (another imprecise term), there are instead infinite shades of grey. Furthermore, severity or even presence of a problem usually waxes and wanes over the years. Again, contrary to popular belief, SUDs are not always progressive. For alcohol use disorder most are not.

But rather than only two or three discreet versions of "problem drinking" (another imprecise term), there are instead infinite shades of grey. Furthermore, severity or even presence of a problem usually waxes and wanes over the years. Again, contrary to popular belief, SUDs are not always progressive. For alcohol use disorder most are not.

3. What else could the committee have done? There was and is no scientific basis for creating two distinct categories. Well, they could have made the cut point higher, such as 5 criteria rather than 2 for a diagnosis. But then that would simply be enshrining the AA ideology into medical diagnosis: you either have it or you don't, it's always severe or it isn't addiction, it's something else. And there would be no impetus to provide treatment for the much larger group of people who have milder forms of the illness and who desire help. They don't go to rehab because who would? It's an obnoxious often toxic treatment with enormous stigma that is terribly inconvenient and expensive. Other alternatives are needed. I believe that over time, people with come to understand that mild SUD is very common, and often self limited, or at least not chronic. In my opinion this will reduce stigma.

4. Finally, the new criteria at least technically will not increase diagnosis of an SUD, especially when it comes to drinking, since almost all cases of alcohol abuse w/o dependence are due to one criterion: admitting to drinking and driving (no DUI.) All other abuse criteria only occur among people with severe chronic addiction. How this is used in practice will become clear over time. My guess is that there will not be a significant increase in clinicians making diagnoses, although there should be. There should be because mild alcohol dependence is unrecognized and not diagnosed or addressed. So I think the same severely addicted people who are are now clinical diagnosed will continue to be.*

*A new study was published online 1/24/13 that shows very little change in overall prevalence of alcohol use disorder between DSM-IV and DSM5 diagnoses. I'll have more on that article later.

MW

Monday, January 28, 2013

DSM5 Substance Use Disorders 1: Advance or Retreat?

I recently had a (friendly) exchange with Maia Szalavitz on the changes to the diagnosis of substance use disorders in DSM5. She and I disagree as to what is likely to happen, and whether DSM5 is a step forward or backward, although we agree on the eventual goal of reducing stigma and making treatment more accessible in more places and with more choice concerning the type and format of treatment offered.

Here are some of my thoughts about the changes in diagnosis in DSM5. This is Part 1 from an email reply to Maia.

1. First, is addiction a disease? Well, of course it is. it's hereditary, has a predictable onset, course, complications and characteristics. It causes people great harm and even death. It is a disorder of brain regulation of ingestive behavior, similar to eating disorders. Two ideas can make this assertion seem less clear.

The first is that disordered behavior is caused by something other than a disordered brain. Western analytical philosophy and religions have asserted that there is a "mind" or "soul" that is not produced by a brain, but there certainly is no evidence to that effect. Try behaving or thinking or feeling without a brain. What is the function of a brain? Besides regulating basic physiological functions such as heart rate or blood sugar, it also regulates mood, thinking, perception, memory and behavior. Example: there is an optimal range for mood just as there is an optimal range for blood pressure, temperature or blood sugar. Basically the optimal mood is neither too high nor too low. When the brain/body loses the capacity to regulate blood pressure, we have hypertension. With blood sugar we get hyperglycemia (diabetes) or hypoglycemia. And with mood, we get mania or depression. Depression is almost never a natural response to anything that happens, you've got to be genetically vulnerable. Same goes for ingesting intoxicants. With drinking, for example, there is an optimal range ("moderate" or "social" drinking.) When the brain loses the capacity to regulate intake you get addiction.

The second idea that gets in the way is that we have to pin down the exact pathophysiology before calling something a disease, but there are many/most diseases where we really do not understand them that well. Alzheimer's disease, multiple sclerosis, arthritis, and macular degeneration are all examples. The hang-up is the false distinction between "physical" (e.g. below the neck) and "behavioral or psychological" meaning roughly above the neck. But this is really just a distinction of scale. It seems "physical" if we can somehow see the pathology (including with a microscope, scanner or blood test), but "psychological" (again, meaning non-material) if we cannot. That's why people make the mistake of thinking that being able to detect blood flow changes in the brain means it is "real," but we don't need an fMRI scan to know that something like addiction is real, we already know that from other data.

An additional concern that is often expressed is that calling addition a disease may absolve a person of moral blameworthiness for what they do, such as commit a crime while high. The mistake is thinking that calling something a disease makes it inevitable and out of any control of an individual, and it quickly gets into the question of free will vs determinism. I thought this one through a long time ago and concluded that in practical terms it makes no difference. That is, if in fact everything is predetermined we cannot know that and it simply means that as we deliberate using our "free will" the resultant decision is predetermined. But so what? We still have to go through the process because that's how things work. Even if you try to "opt out" by saying, "Well, I have no control, so I'm not going to do anything" is a decision that itself would have been predetermined, but it is still a "freely made" decision, meaning that the individual can "change her mind" later and "decide" to take a different course. So in my view, a more practical question is: what would be the effect of absolving everyone of responsibility for their actions if they could show their behavior was due to a genetic abnormality or disease? It turns out, for example, that a tendency towards criminality is inherited, and is triggered by serious abuse or neglect in the first few years of life. This event causes changes in gene expression and is irreversible. Should we hold serial murderers responsible because they lack empathy for others, which is not something they had a choice about? Studies of twins reared apart demonstrate that almost all of our personality traits, career paths, preferences, even the way we part our hair is genetically influenced, often to a remarkable degree. Pedophiles don't choose their urges and preferences for small children. Should they be held accountable? I use these examples to point out that on a practical basis, we have to protect ourselves collectively against these destructive behaviors and the people who carrry them out, whether they "have a choice" or "can't help themselves" or not. So, should drunk drivers be prosecuted for their behavior? Should someone who kills a convenience store clerk during a meth binge be held responsible? Should opioid addicts who steal and rob to obtain opioids be held responsible? Obviously, the answer is yes, because otherwise we will end up with a world that looks like Mad Max, or The Congo.

Wednesday, January 23, 2013

Childhood Obesity Leveling Off

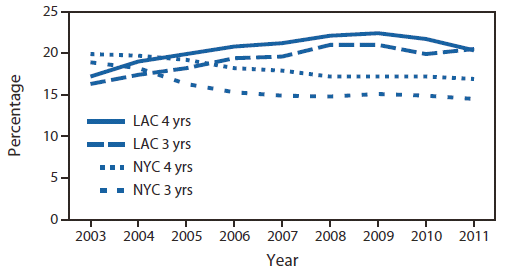

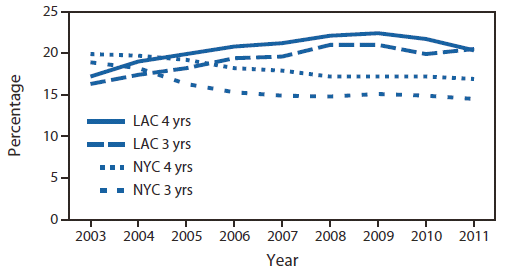

In this week's Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) the CDC reported that childhood obesity among 3-4 year old children in Los Angeles County and New York City has leveled off and even declined a bit. The children studied were receiving public assistance nutritional services under the Women, Infants' and Childrens' (WIC) programs in the two most populous counties in the US. Both jurisdictions undertook programs to educated mothers about proper nutrition and exercise, although New York started earlier. The results are encouraging.

Prevalence of obesity among 3-4 year-olds in LA County and New York City

Ethnicity and obesity

Childhood obesity varies by ethnicity. See the charts below.,

Hispanicstended to have more obesity compared to Blacks, Whites, and Asians. Why this is true is unclear but it is a national trend. Overall, these are encouraging results, suggesting that our increased awareness of diet and obesity, and subsequent educational efforts, may be paying off, at least among low-income citizens.

MW

Prevalence of obesity among 3-4 year-olds in LA County and New York City

Ethnicity and obesity

Childhood obesity varies by ethnicity. See the charts below.,

Hispanicstended to have more obesity compared to Blacks, Whites, and Asians. Why this is true is unclear but it is a national trend. Overall, these are encouraging results, suggesting that our increased awareness of diet and obesity, and subsequent educational efforts, may be paying off, at least among low-income citizens.

MW

Tuesday, January 22, 2013

Our Hysterical Approach to Chronic Pain and Opioids

SAMHSA recently issued a report about addiction program treatment admissions where the primary problem was a combined dependence on benzodiazepine anti-anxiety and opioid pain medications. There has been a marked increase in such admissions, in the face of overall decrease admissions for other psychoactive substances (see chart below.)

Number of admissions for combined benzodiazepine and opioid dependence:

What is interesting is that the prevalence (the proportion of people in the country with a disorder) of each has not risen since 2002. Here is the annual prevalence of opioid and other illicit drug dependence or abuse according to NSDUH data. As you can see, dependence upon prescription opioids has remained stable between 2002 and 2011. What has changed is the number of people presenting for treatment, and deaths due to prescription opioids, both of which have risen dramatically in recent years. It is very likely that the increase in people seeking treatment is a result of the increase in opioid addiction that occurred between 1998 and 2002. Many, if not most opioid addicts seek treatment only after several years of addiction. Thus, there is not a new epidemic of opioid addiction. There is an increase in treatment seeking.

It is important to note the downturn in 2011. Drug epidemics typically end when drug users and, especially, potential drug users become aware of the dangers of using certain drugs, and elect to stay away from the dangerous ones. PCP was once a national scourge, as was cocaine and methamphetamine. Usually, the epidemic starts to wane about the time that there is a national hysteria whipped up about them, and lawmakers typically invoke all sorts of draconian laws amidst many lofty and moralistic statements. Thus, it appears that policies resulted in reduced drug use, but more often, the drug use was decreasing before the policies took effect. That fact, of course, is never acknowledged by the policymakers, but why would they, when their job is to get re-elected?

And just a brief note about proportionality of the problem. In spite of all the hysteria, it is important to remember that cigarette smoking kills almost 500,000 people in the US annually, and alcohol about 80,000. The number of opioid overdose deaths? Recently, the CDC reported that almost 15,000 deaths occurred from opioid overdose in 2008, a number that has almost certainly risen since then. Yes, this is a serious problem that must be addressed. But considering that cigarette smoking causes about 30 times as many deaths helps keep this in perspective.

We are currently in an era of hysteria over an increase in prescription opioid addiction which is already on the wane. Unfortunately, what we can anticipate now are ill-advised, arbitrary and draconian policies to deal with this problem. I'm not suggesting there is not problem; it is a serious one. But by approaching this with hysterical and moralistic fear-mongering and condemnation, we are going to hurt many people, especially people with chronic pain and the physicians who treat them, without necessarily doing much if any good.

Right now, there are a group of moralistic medical scolds with fervent beliefs not supported by solid empirical evidence who have the national attention. The vacuum created by the lack of evidence is filled with hot air and strong opinion, and because their moralistic pronouncements fit with most peoples' prejudices and ignorance, and this country's Calvinistic attitudes, they are accepted without appropriate skepticism. We now have a full-blown witch hunt going on that will result not in appropriate modification of treatment of chronic pain. Instead, it will increase suffering, result in preventable deaths due to opioid overdose, lack of access to appropriate opioid maintenance and mental health treatment and increased suicides among chronic pain sufferers, and destroy the professional lives of physicians who treat pain. There is a better way, but I doubt we will take it.

MW

Number of admissions for combined benzodiazepine and opioid dependence:

What is interesting is that the prevalence (the proportion of people in the country with a disorder) of each has not risen since 2002. Here is the annual prevalence of opioid and other illicit drug dependence or abuse according to NSDUH data. As you can see, dependence upon prescription opioids has remained stable between 2002 and 2011. What has changed is the number of people presenting for treatment, and deaths due to prescription opioids, both of which have risen dramatically in recent years. It is very likely that the increase in people seeking treatment is a result of the increase in opioid addiction that occurred between 1998 and 2002. Many, if not most opioid addicts seek treatment only after several years of addiction. Thus, there is not a new epidemic of opioid addiction. There is an increase in treatment seeking.

It is important to note the downturn in 2011. Drug epidemics typically end when drug users and, especially, potential drug users become aware of the dangers of using certain drugs, and elect to stay away from the dangerous ones. PCP was once a national scourge, as was cocaine and methamphetamine. Usually, the epidemic starts to wane about the time that there is a national hysteria whipped up about them, and lawmakers typically invoke all sorts of draconian laws amidst many lofty and moralistic statements. Thus, it appears that policies resulted in reduced drug use, but more often, the drug use was decreasing before the policies took effect. That fact, of course, is never acknowledged by the policymakers, but why would they, when their job is to get re-elected?

And just a brief note about proportionality of the problem. In spite of all the hysteria, it is important to remember that cigarette smoking kills almost 500,000 people in the US annually, and alcohol about 80,000. The number of opioid overdose deaths? Recently, the CDC reported that almost 15,000 deaths occurred from opioid overdose in 2008, a number that has almost certainly risen since then. Yes, this is a serious problem that must be addressed. But considering that cigarette smoking causes about 30 times as many deaths helps keep this in perspective.

We are currently in an era of hysteria over an increase in prescription opioid addiction which is already on the wane. Unfortunately, what we can anticipate now are ill-advised, arbitrary and draconian policies to deal with this problem. I'm not suggesting there is not problem; it is a serious one. But by approaching this with hysterical and moralistic fear-mongering and condemnation, we are going to hurt many people, especially people with chronic pain and the physicians who treat them, without necessarily doing much if any good.

Right now, there are a group of moralistic medical scolds with fervent beliefs not supported by solid empirical evidence who have the national attention. The vacuum created by the lack of evidence is filled with hot air and strong opinion, and because their moralistic pronouncements fit with most peoples' prejudices and ignorance, and this country's Calvinistic attitudes, they are accepted without appropriate skepticism. We now have a full-blown witch hunt going on that will result not in appropriate modification of treatment of chronic pain. Instead, it will increase suffering, result in preventable deaths due to opioid overdose, lack of access to appropriate opioid maintenance and mental health treatment and increased suicides among chronic pain sufferers, and destroy the professional lives of physicians who treat pain. There is a better way, but I doubt we will take it.

MW

Monday, January 7, 2013

Counseling Adds Nothing to Buprenorphine Alone for Opioid Addiction

In a surprising new study, David Fiellin and his colleagues at Yale found that adding cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) to buprenorphine plus medical management along did not change outcomes. That's right, folks, nothing. This adds to the growing evidence that the primary reason people get better with Suboxone (buprenorphine is the primary ingredient) is the drug not the counseling. In another recent study, Roger Weiss and colleagues with the NIDA Clinical Trials Network found that the intensity of counseling made no difference in outcomes. Of course, they also found that after 11 weeks of Suboxone maintenance, when subjects were tapered off, the relapse rate within 8 weeks was more than 90%.

Here's a graph showing the final comparative outcomes. Note that in the first 12 week, pharmacotherapy management along (PM) actually had better outcomes, although not significantly so.

This will be hard to hear for many who are deeply committed to and believe passionately that it's the other way around, that counseling is the primary ingredient of treatment. That's why SAMHSA and others have tip-toed around this issue, calling treatment with Suboxone or methadone (another drug used to treat opioid addiction) Medication Assisted Treatment. Well, guess what? With opioid addiction it's the other way around: Counseling Assisted Medication. Or maybe: medical treatment with counseling as needed for problems other than opioid addiction. Hhhhmmmm. Sound familier? Let's see now, isn't that how we treat diabetes, hypertension, heart disease, stroke, allergies, whatever?

So for all you flat-earthers out there who cling to 12-Step or other counseling as the Holy Grail, I suggest you consult The Farmers Almanac, your horoscope, the I Ching, tea leaves, Tarot cards and the Mayan Calendar for guidance. Because you certainly don't seek any from science.

MW

References:

Here's a graph showing the final comparative outcomes. Note that in the first 12 week, pharmacotherapy management along (PM) actually had better outcomes, although not significantly so.

This will be hard to hear for many who are deeply committed to and believe passionately that it's the other way around, that counseling is the primary ingredient of treatment. That's why SAMHSA and others have tip-toed around this issue, calling treatment with Suboxone or methadone (another drug used to treat opioid addiction) Medication Assisted Treatment. Well, guess what? With opioid addiction it's the other way around: Counseling Assisted Medication. Or maybe: medical treatment with counseling as needed for problems other than opioid addiction. Hhhhmmmm. Sound familier? Let's see now, isn't that how we treat diabetes, hypertension, heart disease, stroke, allergies, whatever?

So for all you flat-earthers out there who cling to 12-Step or other counseling as the Holy Grail, I suggest you consult The Farmers Almanac, your horoscope, the I Ching, tea leaves, Tarot cards and the Mayan Calendar for guidance. Because you certainly don't seek any from science.

MW

References:

David A. Fiellin, MD, Declan T. Barry, et al., A Randomized Trial of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy in Primary Care-based Buprenorphine. The American Journal of Medicine, Volume 126, Issue 1, January 2013, Pages 74.e11–74.e17

Weiss, R. D., J. S. Potter, et al. (2011). "Adjunctive Counseling During Brief and Extended Buprenorphine-Naloxone Treatment for Prescription Opioid Dependence: A 2-Phase Randomized Controlled Trial." Arch Gen Psychiatry: 68: 2011-2121.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)